Difference between revisions of "Multi-Modal Memory Restructuring for patients suffering from a Combat-Related PTSD"

(→About) |

(→About) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Multi.jpg]] | ||

== About == | == About == | ||

Revision as of 13:28, 29 April 2010

Contents

- 1 About

- 2 Introduction

- 3 Research question

- 4 Proposed system

- 5 Research methodology

- 6 Revised scenarios (PTSD among soldiers)

- 7 Early concept screens

- 8 Early concept screens (therapist side)

- 9 New concept to explain features

- 10 Improved concept screens

- 11 Improved prototype after more feedback (formative)

- 12 Version 0.2 3D editor feature

- 13 Photos Case Study with real patient

About

Research on: Multi-Modal Memory Restructuring for patients suffering from a Combat-Related PTSD

Literature study and thesis by: Matthew van den Steen

Started: November 2008

Ended: April 2010

Introduction

War is known for its high rates of potential stressors. Fire fights, terrorist attacks, losing comrades and taking care of dead bodies are only some of the events a soldier is exposed to during war. A study (Hoge, et al., 2004) among ‘Operation Iraqi Freedom’ veterans concluded that up to 18% of the returning soldiers were affected by traumatic experiences and exhibited PTSD symptoms. Another study (Milliken, Auchterlonie, & Hoge, 2007), also concerned with returning soldiers from Iraq, has shown that over 66% of the soldiers were exposed to potential stressors. The same study reported that almost 17% of active duty soldiers and over 24% of reserve soldiers screened positive for PTSD. When soldiers or other military personnel get deployed multiple times, the chance of developing a PTSD multiplies by a factor of 1.5. Other reports (Garcia-Palacios, Hoffman, Carlin, Furness, & Botella, 2002) have shown that a large number of people do not seek treatment, unless the disorder causes drastic changes in their lifestyle. People tend to rather avoid various stimuli then seek appropriate treatment (Emmelkamp, et al., 1995). A reason mentioned by Hoge (2004) is the stigmatization attached to the treatment, causing soldiers to experience anxiousness towards possibly losing their jobs or facing others who know about their treatment.

Another issue is requiring data needed for treating patients with combat-related PTSD. The therapist needs information about the deployment and the problematic stressors in order to address them. Some patients are not willing to go into detail as some events may be too painful to remember. It is also possible that the patient does not recall what happened accurately or does not feel required to share aspects related to a particular time period. Of course therapists have acquired general data about a deployment through an intake session and reports, but this is often not sufficient. The therapist needs to let the patient re-experience, relearn and reappraise past events in order to process the traumatic ordeal.

Two effective methods to treat combat-related PTSD are ‘Cognitive Behavior Therapy’ (CBT) and ‘Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing’ (EMDR). However, a recent review (Schottenbauer et al., 2008) reports high drop-out rates for both CBT and EMDR. The risk of a patient not receiving sufficient treatment adds up because of patients who are not willing to finish their treatment. This has lead to the exploration of new emerging treatment methods to help patients with a combat-related PTSD as well as to increase appeal relative to traditional face-to-face therapy (Cukor, Spitalnick, et al., 2009). One such treatment is Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET). It allows therapists to gradually expose patients to distressing stimuli in virtual scenarios using computer assisted technology. An unexplored field is the use of computer assisted technology to support trauma-focused psychotherapy. The emphasis is on restructuring and reappraising memory elements. The exploration and design of a system that allows the patient to re-experience, restructure and reappraise particular moments of a past deployment is the main focus of this thesis.

Research question

The initial idea was to let the patient recreate a particular setting from the past by adding and rearranging 3D models in a virtual world. This allows patients to better explain what they experienced and to rethink of what they thought that happened is really true. At that time VRET was the only treatment that used computer assisted technology to treat patients with a combat-related PTSD. VRET also showed similarities with the concept as it puts the patient in a virtual representation of the real world. With VRET, however, the focus is not on restructuring and relearning. Patients can talk about what they experienced, but the patient is not given any tools to flexibly facilitate memory. Although analyzing VRET was found to be useful when designing the new system, it did not provide sufficient information to see if treatment would really benefit from the new envisioned approach. The envisioned system is a new concept and therefore needs a thorough domain analysis to obtain the knowledge required to establish a first requirements baseline. The research question of this thesis is as follows:

Is it possible, and what is required, to enhance the treatment of combat-related PTSD, focusing on the restructuring and relearning of a past event, using computer assisted technology?

Only an analysis is not sufficient to properly answer the main research question. Various expert reviews are necessary and several prototypes of the 3MR system have to be built to evaluate, verify and refine the initial obtained requirements baseline.

Proposed system

In traditional group therapy patients talk about their past deployments and share their experiences with each other in the presence of a therapist. In these situations pen, paper and a flap-over are used to allow patients to express themselves better. Also, memory is often compromised and due to memory distortions or amnesia for details these facilities can help the patients to remember and rethink about what happened. The envisioned application, the Multi-Modal Memory Restructuring (3MR) system, takes this a few steps further. The 3MR focus does not lay on direct exposure, but on the way patients facilitate and manage their memory to restructure and relearn about their past experience involving the problematic stressors. The system allows patients to organize various deployment-related multimedia elements on a set timeline. Of course by managing these multimedia elements there is a chance that the patient will be exposed to past traumatic events from the past.

One of the advantages of this approach is that patients now have the flexibility to rearrange content themselves and add more memory elements as the overall therapy progresses. Letting patients accomplish this by using their own material, such as personal photographs and geographical maps, and linking those to a specific day could provide a more effective way of restructuring and discussing their past experience. False memories, such as the order of events and the location of a particular stressor, can be addressed and forgotten memories may be triggered. Using a timeline which keeps track of the personal progress may even encourage patients to add more details and continue with the treatment. Another possible advantage is that the use of personal data can result in a different perception of the, often seen as problematic, deployment; good memories can be triggered of events not directly related to the stressors. These memories are often forgotten as the focus is mainly on the problematic events which occurred during that time. The additional option to let patients create a virtual representation of the real world in 3D allows them to rethink about the event to see if everything they remember is (sequentially) correct. The system is designed for use in a group therapy, but can easily be adapted for a single patient-therapist setting. When the system is used in a group therapy setting, it can provide an easier and more efficient way of sharing stories with the other patients. This is because everything is projected on a wall for everyone to see. Group members can discuss the events shown on the wall and share similar experiences with each other as part of the treatment method.

Research methodology

The design of the system followed the situated cognitive engineering approach as described by Neerincx and Lindenberg (2008). It is an iterative approach where the requirements baseline continuously changes as new insights are acquired through prototype evaluations and reviews with experts in the field during the entire design process. The first step that has to be taken is a Work Domain and Support (WDS) analysis to establish an inventory of all relevant human factors, operational demands and envisioned technology. Knowledge can be gained by analyzing the current situation, resulting in a better understanding of all involved actors, used theories, activities and the clinical environment. Using the data acquired from this analysis, core functions and claims can be defined and scenarios can be created. This results in a preliminary requirements baseline. Afterwards this baseline needs to be refined and verified which is done in the last phase.

All necessary information needed for the domain analysis was acquired in close cooperation with a military psychiatrist from UMC Utrecht. Additional meetings throughout the study were planned to discuss various scenarios and prototypes.

Revised scenarios (PTSD among soldiers)

<anyweb>http://www.youtube.com/v/NKQRBklDruM&hl=nl_NL&fs=1&</anyweb>

<anyweb>http://www.youtube.com/v/tfzm0SQHo_U&hl=nl_NL&fs=1&</anyweb>

<anyweb>http://www.youtube.com/v/Jc0tHuq4Wow&hl=nl_NL&fs=1&</anyweb>

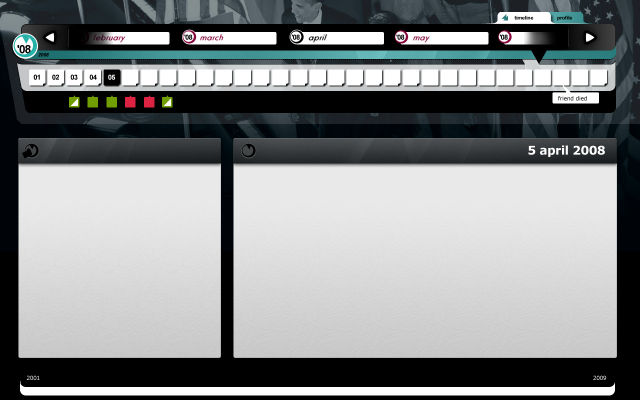

Early concept screens

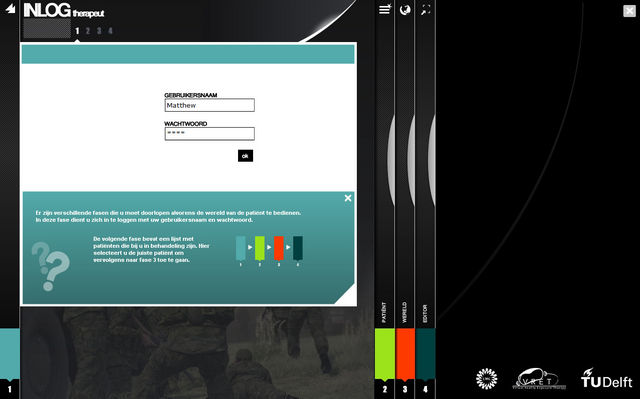

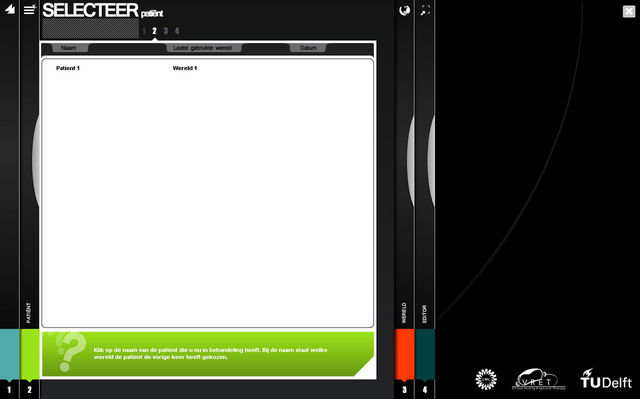

Early concept screens (therapist side)

New concept to explain features

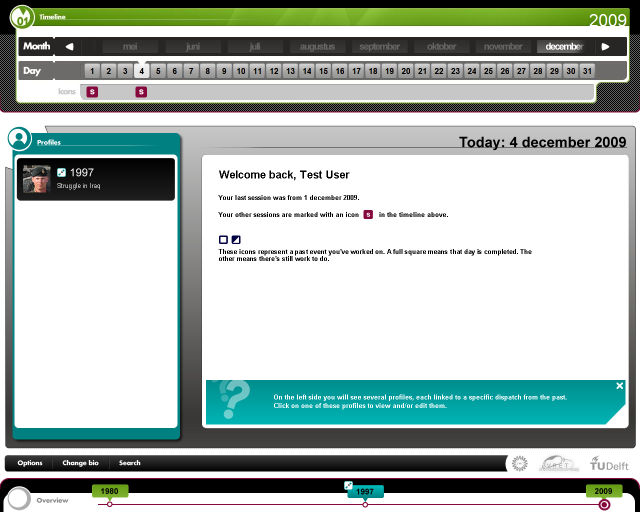

Improved concept screens

Opening view

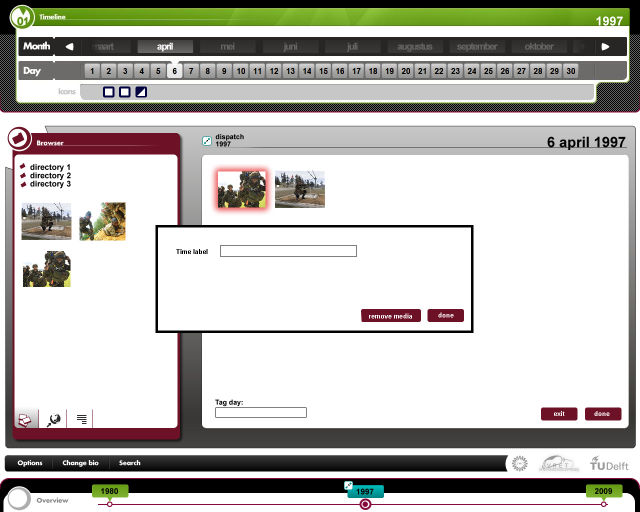

Adding media view

Improved prototype after more feedback (formative)

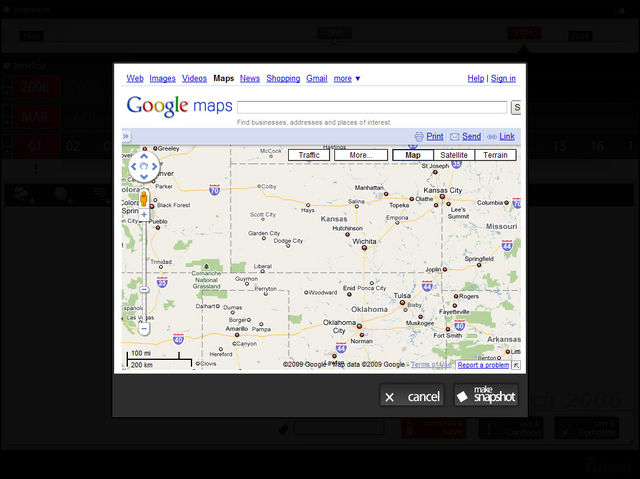

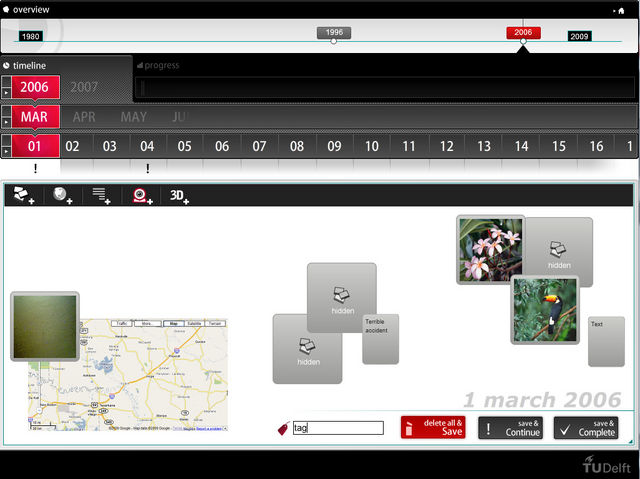

Maps screenshot feature using 'google maps'

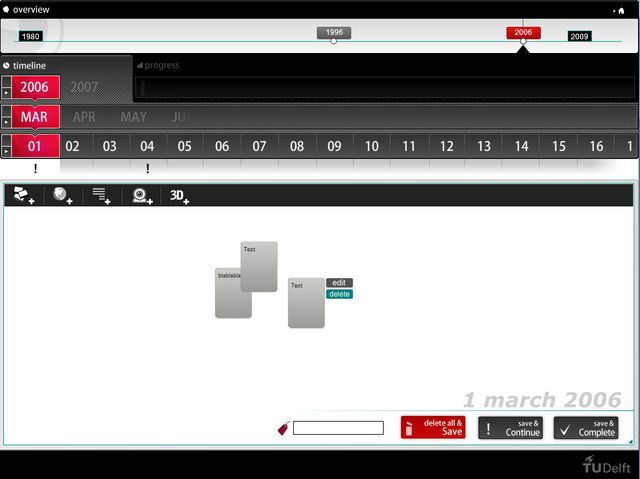

Edit a day (text files shown)

More features shown, such as hiding images and webcam shots

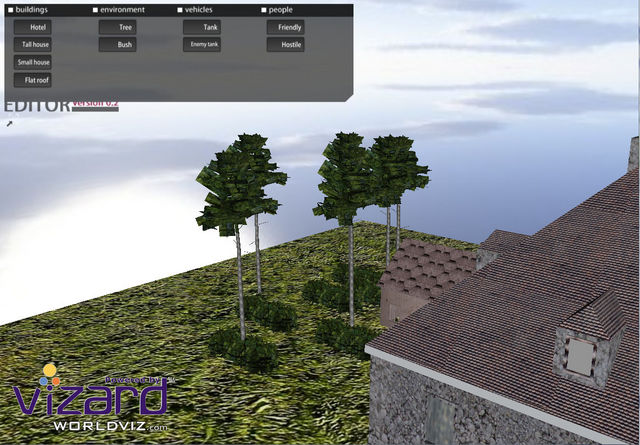

Version 0.2 3D editor feature

Photos Case Study with real patient

Emmelkamp, P.M.G., T.K. Bouman, and A. Scholing, Anxiety disorders: a practitioner's guide. 1995, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Hoge, C. W., Castro, C. A., Messer, S. C., McGurk, D., Cotting, D. I., & Koffman, R. L. (2004). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. [Article]. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(1), 13-22.

Milliken, C. S., Auchterlonie, J. L., & Hoge, C. W. (2007). Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. [Article]. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association, 298(18), 2141-2148.

Garcia-Palacios, A., Hoffman, H., Carlin, A., Furness, T. A., & Botella, C. (2002). Virtual reality in the treatment of spider phobia: a controlled study. [Article]. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(9), 983-993.

Schottenbauer, M. A.; Glass, C. R.; Arnkoff, D. B.; Tendick, V., and Gray, S. H. (2008) Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry. 2008 Summer; 71(2), pp. 134-68.

Cukor, J., J. Spitalnick, et al. (2009). Emerging treatments for PTSD. Clinical Psychology Review 29(8): 715-726.

Neerincx, M.A. & Lindenberg, J. (2008). Situated cognitive engineering for complex task environments. In: Schraagen, J.M.C., Militello, L., Ormerod, T., & Lipshitz, R. (Eds). Naturalistic Decision Making and Macrocognition (pp. 373-390). Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited.